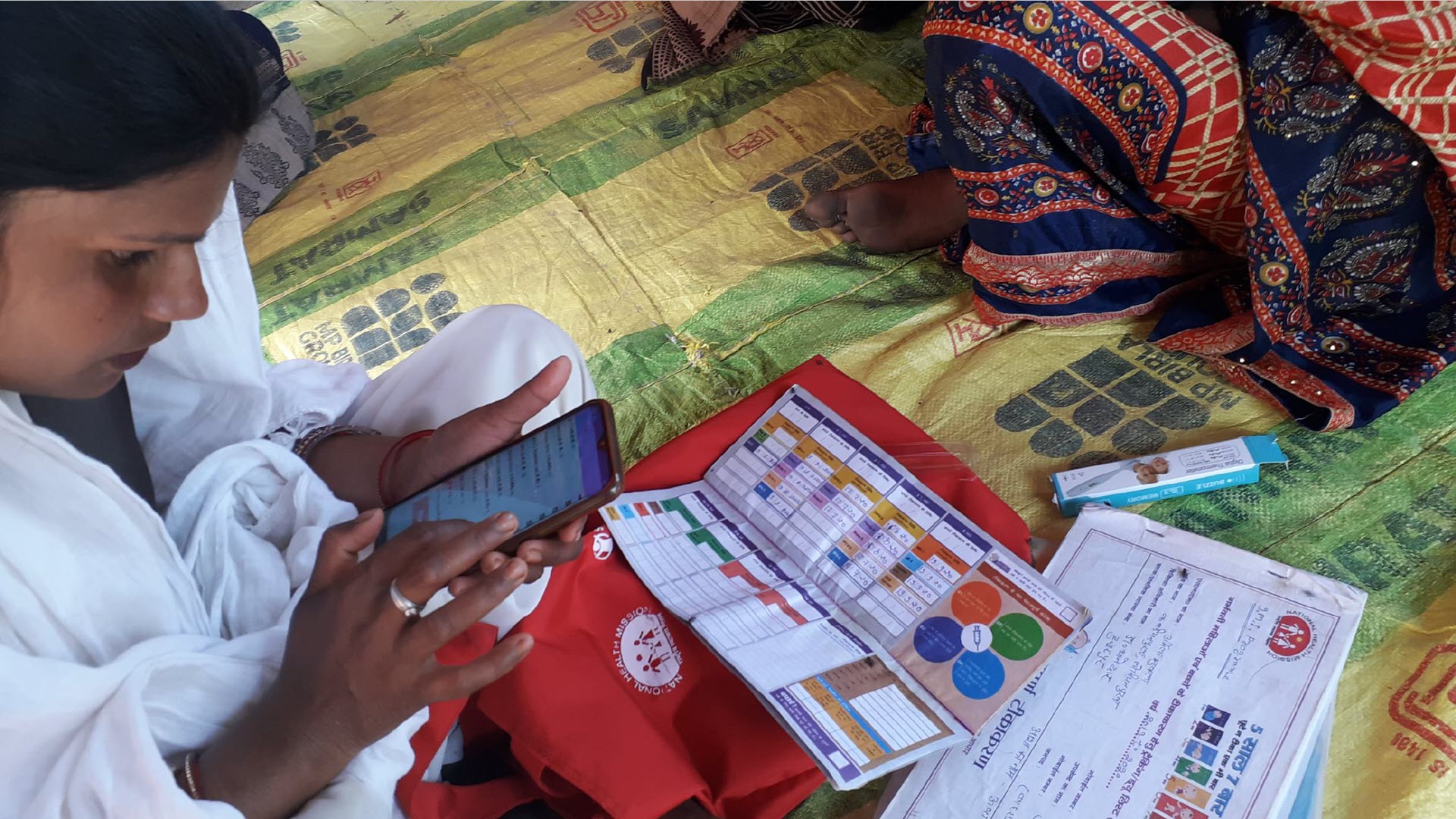

It is a scene that Abdulkadir presented during the webinar to illustrate how community health workers can be empowered with the right tools. The outreach kit was part of an integrated community-based health strengthening approach she led in a 2-year project with the Philips Foundation, which focused on enhancing the role of community health workers. In addition to making technology available, health workers were trained and mobilized to collect and use health information data systematically.

According to Abdulkadir, the project enabled community health workers to deliver their tasks more effectively. “It enhanced their confidence levels, augmented their earlier education and increased community acceptance. This has led to concrete improvements in outcome in terms of household visits, referrals, demand for services and skilled birth attendance.”

Indispensable, yet underutilized

Universal healthcare coverage is still a far cry from being realized. With half of the world population still lacking access to essential health services, it is estimated that a total of 18 million health workers will be needed to meet at least that minimum quality of care [1][2]. There is widespread consensus [3] that the highest impact can be reached with community and population-based care, as this can cover the majority of healthcare needs, including prevention, early diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care.

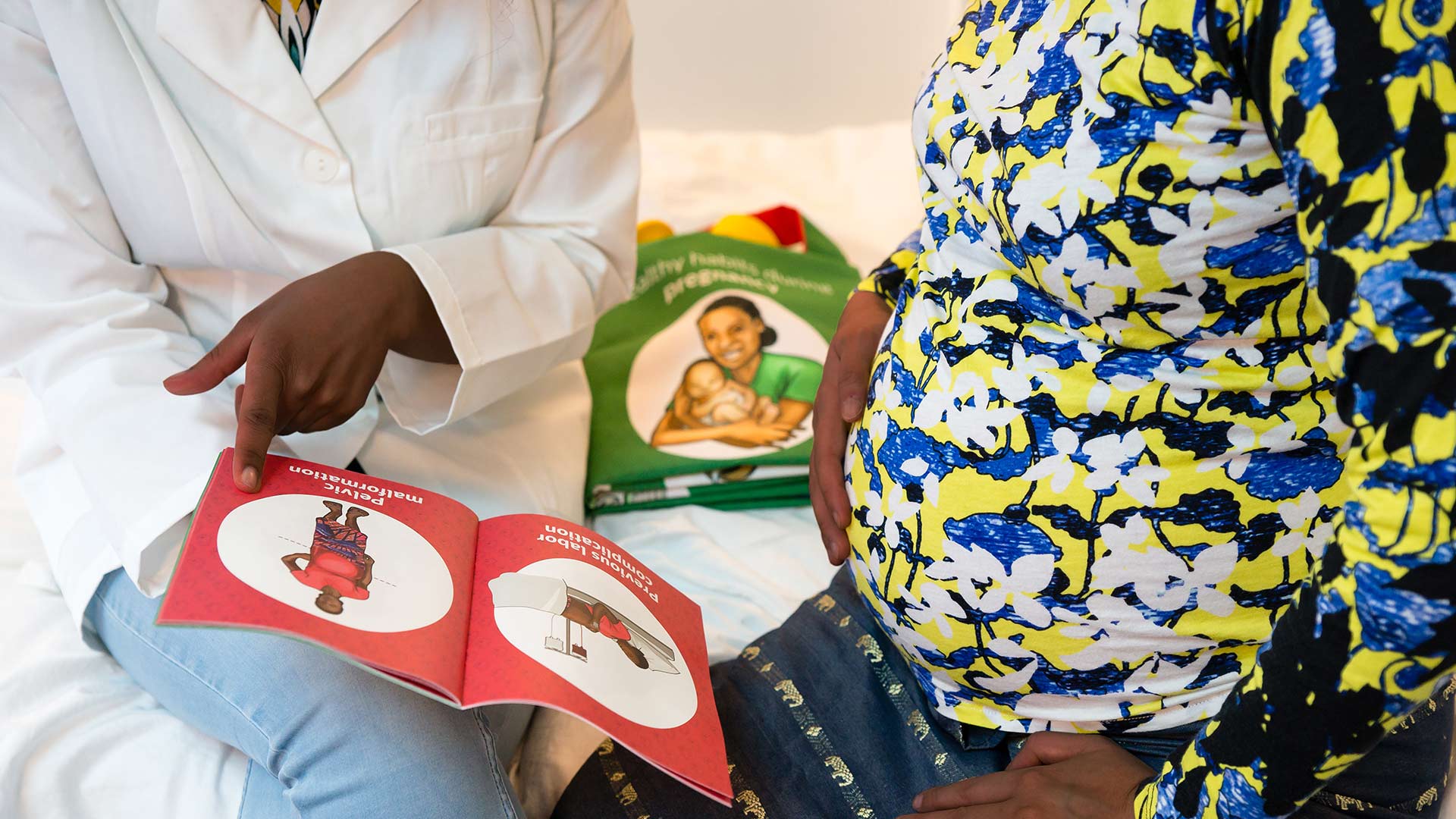

Community health workers play an indispensable role in strengthening community and population-based healthcare throughout the world. People with basic qualifications or limited health backgrounds can be effectively trained and equipped to undertake selected tasks of professional health workers. Working as volunteers in the community, on stipends or with other forms of informal support, community health workers help bring healthcare to communities that otherwise would not receive it, and at the same time, they relieve the burden on overstretched professional health workers. Despite their informal status, community health workers can significantly impact patient health, such as improving outcomes of mother and child care or addressing the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, or heart conditions.

Yet despite their recognized significance, the potential of community health workers is underutilized. They are often poorly equipped and lack necessary training and education. In addition, limited payment and career prospects can lead to retention challenges.

Can technological solutions help change that? We believe so.

It’s all about behavior change

In a country-wide campaign of Save the Children in partnership with the national and state governments to fight childhood pneumonia in India, community health workers [4] play a key role in educating rural villages about prevention, as well as recognizing symptoms and seeking care in case of suspicious signs. In a project with Philips Foundation and the Philips India CSR program, Save the Children is now pioneering the use of mobile digital health tools to support community and next-level health workers in these important and educational tasks, as well as with subsequent management of positive cases.